Злий дух вийшов чорним димом з лона землі і огненною хмарою полинув понад Землею

—Леся Українка, Зібрання творів, т. 71

a nascent subjectivity

a constantly mutating socius

an environment in the process of being reinvented

—Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, 68

Intro

Whenever I introduce myself to strangers, the conversation almost always follows the same script. Over the years, my excitement for sharing anything about my home region has dimmed. In the beginning, I was hopeful; I believed that the least I could do was to explain where I had been all those ‘8 years’ some people used to throw around as soon as they heard the word ‘Donbas.’ These encounters still happen, yes, though far more often the conversation drifts into something like this:

-‘So where in Ukraine are you from?’

(a familiar tightening in chest, thinking: ‘where do I start’)

-‘Well, I grew up in Donbas. Have you heard of it?’

Donbas is a construct—mythological, imposed. A term introduced by Soviet authorities to frame the region as no more than a mere resource: a bottomless coal pit, a nothing-was-here-before. I comprehend this theoretically, yet the word has its grip on my heart, inherited and lived. Not just by me. Generations of my family saw the bottom of the coal pit themselves.

Back to the conversation. Once Donbas enters the room, I’m usually met with an awkward silence.

-‘Have you heard of it?’

And then, almost every second person responds with something like: ‘Oh, I’ve heard about Crimea.’

(thinking: ‘God, where have you been?)

-That’s okay, many don’t. And it’s true. Many of us didn’t know, either.

Some are learning only now. Some are unlearning.

And I can only speak for myself.

And then the familiar: Where do I start? slips out of my mouth, it’s been on the tip of my tongue for a long time. Where do I begin? is another one, equally impossible.

How can anyone —I, you, us —locate a beginning inside what has now become more than a decade of what felt like a fin_ish:

to varnish memories

to lacquer childhood photographs left behind

to veneer grief

to coat fragility until it shines

to stain, and to learn to leave stained

to wax nostalgia into woodgrain

enamel

glaze

gloss

burnish a wound until it mirrors back

False start. Then I would have to go on about the timeline, about how my family has been displaced twice, how I cannot see my grandmother in the occupied territory, how my class switched to Ukrainian language in protest, how we planted flowers to the distant thunder of cannonades as russians destroyed the Donetsk airport, how we hastily packed and left, having no faith in the duress of the staged theatre of absurdity. And how naive we were.

In the preliminary stages of our research—that moment when one must finally choose a topic and stand inside, and by it—I was confronted with the question: Where do I even start? again. Beyond the emotional intricacies of my own experiences and the constant worry about not being swallowed by the (ugly) feelings, there also was the sheer multiplicity of ways (some blunt, some insidious) through which occupation sustains itself. During our team calls, we half-laughed, half-cried as we tried to name the shape of it all. We kept returning to the image of an iceberg: the visible tip that can be glimpsed by those who dare to look, and the vastness beneath, obscured by the fumes and smog of the not-yet-exhausted mythologies that Russia keeps producing, resurrecting, transmitting. When it comes to the emotional infrastructures, the task grows even thornier: emotional is hard to hold without breaking; it flashes by in passing, traced mostly in residue. Such work is never complete, but neither is it entirely resistant to capture.

These returns kept tugging at me as we began shaping the project. I realised that what I was doing, late-night walking down my old StreetView path, was not simply remembering. Was it a performance closer to method?

Nostalgize_ing

How can one imagine the capture here? The word itself misleads. It evokes traps and the fantasy of fixing something in place. That would condemn us to the Sisyphean labour of pinning down a world with words that arrive damaged. Instead, let capture be a verb. To capture as to record (never fully), as to catch (what passes), as to hold (someone’s attention? least momentary). It is not so much about possession as it is about noticing fragments, residues, shrapnel as they pass across the surface of the self. Even the act of recording is not an attempt at accuracy. First we narrate something to oneself, trying to make sense out of it, and then to whoever chooses to listen. If there is a ‘catch’ here, I hope it is not representativity but rather surviving bits and moments of survival that rely on your willingness to stay with them.

The methodology is therefore not accidental. Oftentimes possessed, almost always haunted, by fragments of my own childhood in Donetsk, I kept circling the same questions: what myths do we construct to endure? Which memories do we hold onto, and which do we let fall away? A few times a year I open GoogleMaps StreetView and walk my old route to school. The images were taken just before Euro 2012. Time suspended. A Ukrainian flag still hangs above the school entrance. I am almost sure some of my classmates appear in those photographs too, casually walking through a city that does not know yet it is about to fall apart. Just before the time walked over us. One evening I shared some screenshots with others, adding my tentative guesses about who those figures might be. My teacher replied that the resemblance was real, and then another text: ‘(you) nostalgize.’

I suppose she was right.

In Ukrainian, the most common way to express nostalgic feelings is through the verb ностальгувати. The English language carries its own equivalent, to nostalgize, though it appears far less frequently than the phrase to feel nostalgic. What interests me is how nostalgize behaves: it can move in two directions at once, operating both transitively and intransitively—a hinge between doing and feeling.

- (transitive) To treat something nostalgically. To nostalgize a place, to act upon it, to attempt, perhaps, to territorialize loss.

- (intransitive) To revel in nostalgia. An affective relation-in-motion, perhaps, without object.

This dual movement mirrors the methodological terrain of counter-cartography, which refuses to pin memory to fixed coordinates, instead, paying attention to what persists, flickers, recurs. In this light, nostalgia is more than a simple return to the past. It becomes a lived and unfinished negotiation between presence and loss, between object and trace, between body and world. This offers a method of spatial becoming, in which memory is felt as motion.

Counter-mapping follows a similar logic of negotiation. Whereas conventional cartography historically enacted what Edward Said called ‘the act of war,’ securing territory through legibility and control (Said 1996); counter-cartography works to loosen those chains of representation. It treats the map as virtual, speculative, and solidaristic, allowing it to exceed its own edges. In Deleuze and Guattari’s terms, the map becomes ‘an experimentation in contact with the real’ (1980, 72). When practiced critically, these emergent maps claim authorship from below; through felt, situated, and relational.

This project therefore understands space as lived, neither fully objective nor purely subjective, but made and unmade through experience. As Baier (2020, 88) writes, a beach is simply ‘beach’ until a shell cuts the foot and ‘our world dissolves.’ Space, then, is ever-shifting, conditioned by sensation, rupture, embodiment, and event. If ‘to share a memory is to put a body into words’ (Ahmed 2004), then counter-mapping becomes a practice of re-embodiment: a spatial choreography in which memory and matter co-produce meaning. Thus, through the process of mapping, participants’ recollections act as ‘memoryscapes’ (Reavey 2017), where narratives and material traces occupy and activate space-time. Memory then exceeds the constraints of the archival to birth movement. As Loveday reminds us, each remembering reconstructs the moment anew: a continuous, iterative re-composition is and through the body (Loveday 2018, 64).

Workshop setting

Two participants sat at the table on a Saturday afternoon. The workshop took place in the Ukraine House in Denmark: a place that, simply by its name, held more than we could unpack in a day. In Ukrainian, there’s no real difference between ‘home’ and ‘house.’ Ukrainians in Copenhagen call it dim—home. That has always felt fitting. All three of us shared, in different ways, the experience of having lost one.

It was one week into August. Behind the thick whitewashed bricked walls, which one participant affectionately compared to a mazanka (a traditional technique used in Ukrainian village houses), there were other rooms filled with volunteers. We were separated by a heavy gray curtain, which amidst the reassurance of the walls’ sturdiness, offered little resistance to sound coming through: paintings being moved, nails meeting walls, a thread of conversation at distance. These noises became an ambient accompaniment to our workshop and, unbeknownst to us then, to what would soon become Uncurtained, an exhibition of Ukrainian art from private Danish collections.

Following Glissant’s proposition that difference is not what divides but the elementary particle of relation (Glissant 2010), I designed the workshop not to smooth experience into sameness but to see what might surface between us. And here they were: two participants from different regions, each carrying their own history, her own timbre of displacement. I hadn’t known how many people would come. I was seeking neither mirrors nor opposites. I had hoped for at least one. And there they were. Two.

(Counter)-mapping became the place where we could meet and work together. Rather than asking participants to recount their stories in chronological order, the map gave them a surface to approach memory sideways. What emerged was proximity. Memories were welcomed through images, smells, sounds. And the map let them, no demand for coherence. Their hands traced different paths. Sometimes those lines met, briefly. The slight friction between memories became the material to work with, layer upon layer. Scarring, scoring, rejoining. Folding, and sealing again. This was our process of inventing a grammar to move through what persists, beyond merely representing what was.

Methodologically, this work responds to MacDougall’s question of ‘Whose story is it?’ (MacDougall 1998). No single narrative could anchor the space, and the workshop proved it. It attended to what Gordon calls ‘complex personhood’ (Gordon 2008), letting vulnerability, imagination, and resilience sit alongside one another, outside the illusory demand for a single interpretative frame. Mapping made it possible for loss to be present, yet only as one strand rather than a totalizing narrative. (Murrani, Lloyd, and Popovici 2023). In this way, nostalgizing becomes a counter-mapping method that intervenes in the politics of space, making room for other temporalities, other forms of presence, and other worlds to be sensed and articulated. The workshop prompts were designed around a series of productive tensions: memory as object (an artefact brought from home if such remained) and memory as atmosphere (day/dreaming exercise using smell and sound as aiding tools in memory recollection); place as territory (re-creating a hometown’s map from memory) and place as lived trace (altering ‘official’ maps). These frictions shaped the process by offering a syntax for mapping corridors, drifts, and shared terrains of what remains in-between past and present. What emerged was an assemblage in which chronology loosened and lost relevance (next) to embodiment.

Bachelard (1969: 6-7) imagines the house as a site that ‘shelters daydreaming’ and ‘allows one to dream in peace.’ On the other hand, displacement unsettles this premise entirely. For the displaced, dreaming often arrives through rupture, in moments when memory slices into the present without warning. The house, in this constellation, is no longer a cradle but an absence, defined by what is ‘no longer,’ and replaced by what slips.

What can the body bear to return to? Perhaps ‘a larger world than our ego recognises’ (Bachelard 1969). Perhaps only a wound, reopened briefly.

Ethical considerations were central to this project, particularly around the risk of retraumatisation. While it was never a condition for participation, both participants had been displaced during the first wave of Russia’s invasion in 2014. Returning to these memories meant engaging with what may have been partly sedimented although still unresolved. One participant noted that time had afforded her partial distance, helping to approach some moments with greater openness. And yet, this cannot be assumed for all. For others, particularly those more recently displaced, such proximity can feel claustrophobic, as if one were held inside an open wound, with no coordinates yet found and no language yet available.

In this sense, the workshop was shaped as much by what could be said as by what could not: silences, hesitations, and pauses. Closure was never the end goal. Here, I draw on Samuel Mutter’s (2025) notion of ‘negative mobilities,’ signifying encounters that ‘may not take place,’ and where the absences, suspensions and refusals hold their own ethical weight. To engage ethically, then, is to acknowledge what remains inaccessible. The aim was to create a space where the ‘may not’ could be honoured, to allow withdrawal, stillness, or the surfacing of difficult (even ugly) responses. In Sana Murrani’s terms, the process of counter-mapping revealed itself as gradually reparative, helping to ‘shift post-traumatic recovery towards a sense of self-realisation and belonging.’ Through the gentle re-encounter with memory through spatial, material, and de/re-centering of narrative, mapping became what James Corner calls ‘a finding that is also a founding.’

World-taken-from-us

To work from the position of a world-taken-from-us is to acknowledge a terrain shaped by absence, dislocation, and limited visibility. It is a world no longer fully available to representation (if it ever was), and one intensified by violence, time, and loss. The world-taken-from-us is my attempt to name the hollow of a wound that once held the shape of home. I borrow here from Eugene Thacker’s notion of the world-without-us, ‘a nebulous zone that is at once impersonal and horrific, making itself felt in the inaccessibility of the world-in-itself’ (2011, 6).

To speak of a world taken from us is to accept that knowledge available for capture arrives in residue—through cracks and in places where meaning falters, and where the more-than-human begins to speak on their own terms. This work proceeds through fragments, as a way of registering discontinuity without rushing to resolve it, of noticing what still leaks and what holds still, even when the surface appears frozen or uninhabitable.

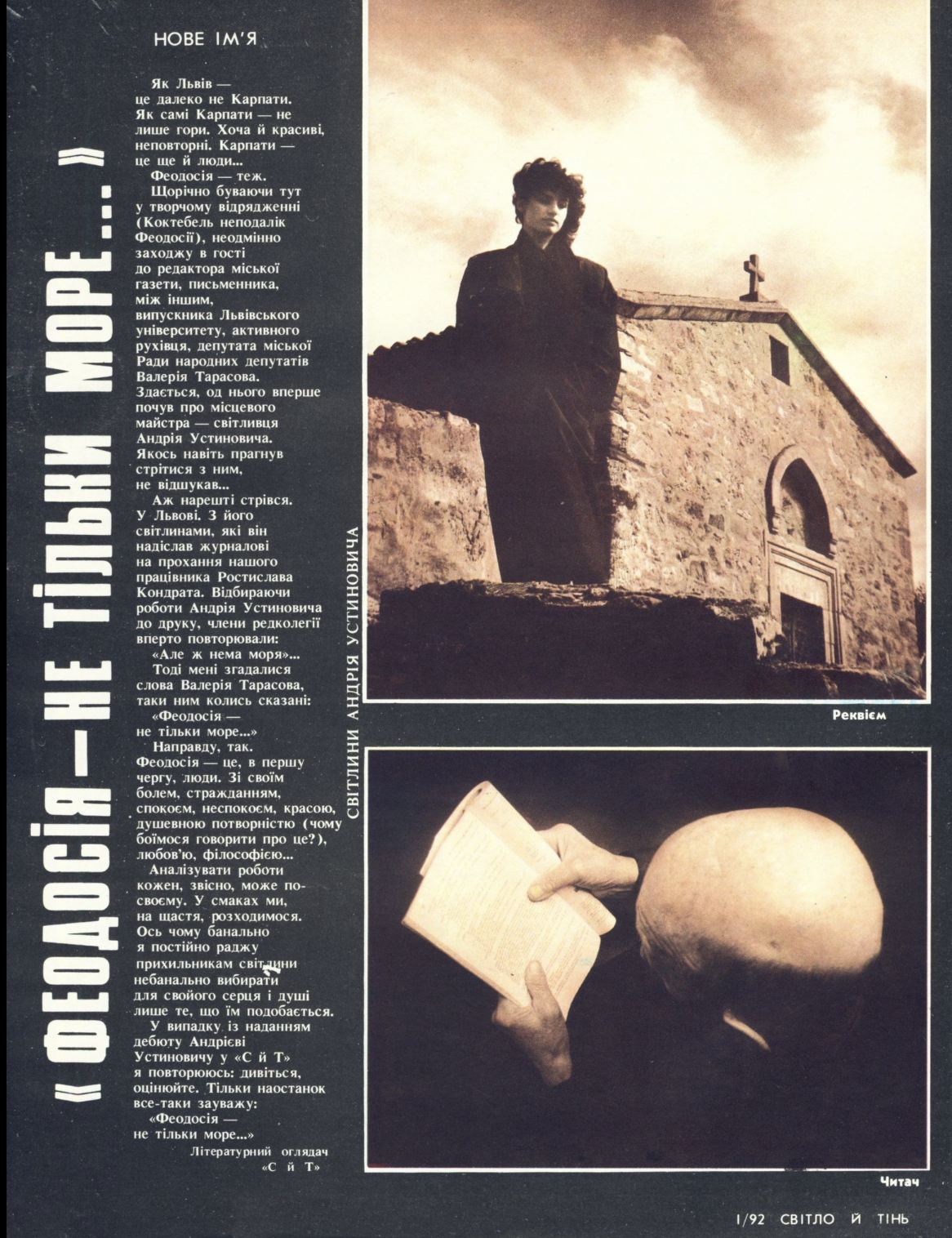

In a short review from Svitlo y Tin’ (1992), from Ukrainian—Line and Shadow, one line stayed with me: “Feodosiya is not only the sea.” It was the author’s insistence that place is never just place. I read it as a call to notice shadows of, and perhaps shed light, on the people who (used to) inhabit it as well as their pains and gestures.

Tr. (editor’s version, redacted):

Just as Lviv is far from being only the Carpathians.

And just as the Carpathians themselves are not only mountains,

However beautiful, however unique.

The Carpathians are also the people…

So is Feodosiya.

Andriy’s home gathered people whom even strict censorship could not frighten away.

As more trust was given to his judgment for publication, he stubbornly repeated:

‘But it’s not only the sea!’

On the contrary: Feodosiya is, first of all, people.

With their pain, suffering, calm, unrest, beauty, spiritual repetition (as they say),

And their love of philosophy…

(….)

That is why I so often and so simply advise young photographers

Not to rush when choosing what their soul likes (….)

You will likely find what succeeds, evaluate it.

But finally, I will still note:

Feodosiya is not only the sea.

Places rarely (if ever) are only what we name. Take a wound, for example. If it were only the sea, at least I could learn to swim. But it never returns in a single wave. So much happens underwater, and what reaches us is often what the storm throws back onto the shoreline.

The form to follow takes its cue from this fractured logic of place. The maps, texts, and recorded conversations are uneven, deliberately so. I try to escape hesitation, the soggy swamp that mistakes coherence for meaning. I run so fast I don’t notice the ground shifting beneath me. It becomes slippery, the kind of cold that gets to your bones. My reflection flashes up from below, but I’m still afraid to stop. Until I trip and fall into a frozen puddle. It shatters.

I try to gather the pieces. Some have softened into small stones; others stay knife-sharp. Those are the ones that cut my fingers. I bleed. It may sound strange but there is a relief in finally seeing the wound. Once it is visible, it becomes possible—if only briefly—to acknowledge it has been there all along.

Will there be silence in and around me?

I’ve heard that dreams are maps of their own. What do the dreams remember that our walking selves cannot? To make this method felt rather than merely explained, I offer here a version of the exercise we used during the workshop.

Now you can choose:

Work with an actual dream you once had,

or let yourself daydream on purpose.

Before you rush forward, let your breath find its own rhythm.

We are all just breathing. Quietly.

Let the ache, if it is there, be. Neither chased away nor held too tightly.

We are all just breathing. Quietly.

When you feel ready, close your eyes.

Travel to a place from your past,

It can be real, invented, a mix of both?

It can also be a place your body invented to survive.

Don’t worry about precision.

As if dreams ever did.

What flickers first?

Pause.

A street? A room? A person? A doorknob?

A shadow? A silhouette? A crowd of many?

Let it surface without needing to make sense.

Is there a taste to it?

Now, ask your dream a question.

It can be as strange as you like.

It is your chance to punch back. And it stays between the two of you.

Don’t force an answer.

Notice the sound around you.

Can you hear your own heartbeat?

‘It was so quiet that I felt ashamed of my pounding heart.’

If it happens to you, let it.

Stay here a moment longer.

Ask your dream-self a question, even if it arrives misshapen.

Will the fingers clench behind me? Will the iron hand rattle its old bones?

And if, at some point, you feel yourself dissolving

Into the black darkness,

Just return to your breath.

Stay as long as you like.

Leave when you feel spacious again.

If you’ve got anything at hand. Literally anything. And if you like,

Let your pen wander. Let the paper get stained, cut, glued. Let it grow crooked if it needs to. Let it be empty if that feels right.

Return.

Lesia Ukrainka, Zibrannia tvoriv u 12 tt., vol. 7 (Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1976), 133–135; first published in Skladka(Kharkiv, 1896), 64–68.

“An evil spirit rose as black smoke from the womb of the earth and, as a fiery cloud, swept across the world,” Lesia Ukrainka, Zibrannia tvoriv u 12 tt., vol. 7 (Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1976), translation mine; originally published in Skladka (Kharkiv, 1896) ↩︎